While reporting for the BBC on a shamanic ceremony in Mongolia, the Frenchwoman Corine Sombrun was filled with the sound of the drum, suddenly lost control of her movements and started to howl like a wolf. When she woke up from this incredible trance experience, the shaman explained to her that the spirits had called her and that she had no choice but to follow a training course in Mongolia. For eight years, Corine went back and forth between Mongolia and Europe in order to reach the status of udgan—a Mongolian term for a woman who has received the gift of communicating with nature and its deities and has been trained by a shaman. After this, she contacted researchers to try to better understand trance and the possible clinical applications it could have in medicine. After meeting researchers in Canada, Corine participated in a study on cognitive trance published in 2020 in the journal Clinical Neurophysiology. We talked to the two main authors of this study: Olivia Gosseries, a neuropsychologist, research associate at FNRS and co-director of the Coma Science Group at the GIGA Consciousness at the University of Liege in Belgium; and Audrey Vanhaudenhuyse, a neuropsychologist and researcher at the algology department at the University Hospital of Liege and director of the Sensation and Perception Research Group at the GIGA Consciousness.

01. Living the Trance

MedicalExpo e-magazine: What is cognitive trance?

Olivia Gosseries: Trance is a modified state of consciousness that changes one’s perceptions of the environment and time and space, offering more mental imagery as well as differences in somatosensory experiences. A parallel can be made with hypnosis or meditation which can also be considered as states of modified consciousness, except that in the case of trance it is very much through the body with movements and vocalizations whereas in meditation and hypnosis you stay very still. Some people say that trance provokes the same state and effects as when one takes certain psychedelic drugs such as LSD or psychotropic plants such as ayahuasca in Amazonia, except that it is reached without drugs or plants.

ME e-mag: In your study, was Corine able to control herself and not move as much as she did during her trances in Mongolia with the sound of the drum?

Olivia Gosseries: Yes. In trance induction, she can move and do whatever she wants, and then once she is well into the trance, she settles down and stays still. If she feels the trance leaving, she can re-induce it again. Corine has learned to control her trance, it has been a lot of work for her. The very first time she went to see researchers, it was in Canada a few years ago, she was told that she absolutely had to stay still because she couldn’t come with her drum to their lab and get an encephalogram. So she trained herself to be able to self-induce the trance by her own will, without needing the drum, and to stay still. When we use an electroencephalogram the participant must stay still because if they move we get movement artifacts and the cerebral signal is drowned out and we can’t see anything.

In the experiment that we carried out with Corine, she induced her trance for two minutes by making a noise and then vocalizations, she moved her hands with very particular motion. After that, her breathing changed, it became very slow, and Corine remained motionless. We were able to start the stimulation of her brain. Her trance lasted about fifteen minutes, but it can last much longer. She explained to us that she was an ant, she climbed a tree and fell out. She had visions of insects and large lizards and she transformed herself into an iguana. Then her tongue began to stick out with the sensation of a turtle’s tongue, there were hissing snakes all around and she transformed herself into all the reptiles, with a feeling of joy and the desire to laugh.

02. Looking at the Brain

ME e-mag: How did the study go?

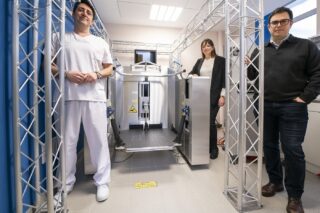

Olivia Gosseries: When you do studies like this, you usually start with one person and then, in a second step, you do a group study. So we started with Corine who came to Liege in 2018 to participate in our different research protocols. First, we did an electroencephalogram (EEG) session with and without trance. Then, we did the same thing with a PET-scan where we inject a radiotracer that acts like glucose and then we look at which regions of her brain use the most glucose or not. Then we did an MRI session to look at the differences in oxygen consumption. And finally, we did a TMS-EEG session (transcranial magnetic stimulation coupled with electroencephalography) where we stimulate the brain and see what cerebral reactions occur in terms of electrical activity. It is a machine with a coil that is placed on the skull and sends magnetic stimulations to this very specific location. The magnetic stimulation induces an electrical impulse that we can observe in the brain. So we did around 300 stimulations in the frontal region of her brain and 300 stimulations at the back of her brain. This first study that we published is on TMS-EEG only.

ME e-mag: What were you able to show with this TMS-EEG?

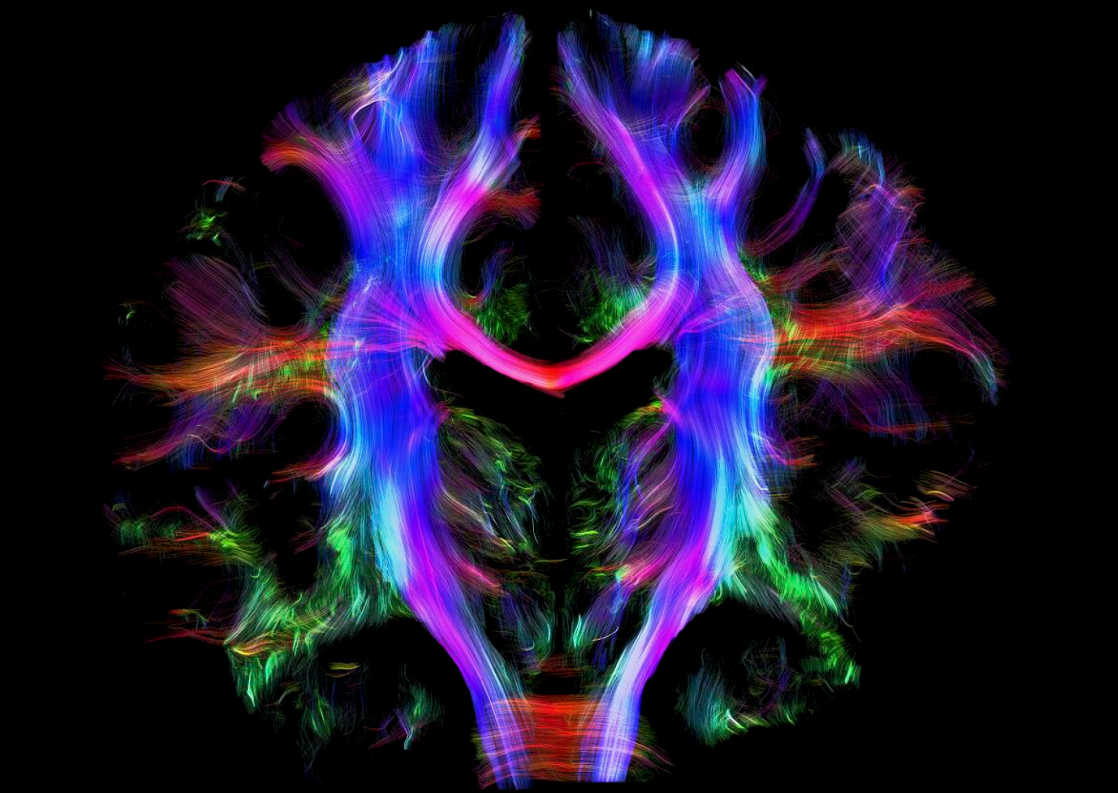

Olivia Gosseries: We use this technique, in general, to diagnose the level of consciousness in patients who have suffered a coma. For example, we have shown that all unconscious people—whether they are in a vegetative state (now referred to as unresponsive wakefulness syndrome) or sleeping without dreaming or under general anesthesia—we can see that the brain reacts to the stimulations but the response is like a slow wave and limited to the location we stimulate, it does not spread throughout the brain. On the other hand, in conscious people—whether they are awake or dreaming (because when we dream we have subjective experiences and therefore we remain conscious even though we are not awake) or have transitioned into a minimally conscious state, i.e. who have recovered signs of consciousness after a coma but cannot communicate—we see that the response is complex and spreads throughout the brain. All of this, we know already.

Now, we are asking ourselves, what about when we are conscious but in a state of modified consciousness, such as trance? And here we observed that the response of the brain is also complex but that when we stimulate at the front of the brain, the response is clearly increased and amplified compared to this same situation when the subject is not in trance. On the other hand, when we stimulate at the back of the brain, the response of the subject’s brain is diminished compared to when he or she is not in trance. This is interpreted in the sense that it is a cognitive trance and the front part of the brain is essentially dedicated to attention, to focus, to the executive functions. The back of the brain is more related to perceptions, to the external environment.

03. Comparing Trance to Hypnosis or Meditation

ME e-mag: Did you also take measures that are used in hypnosis for example?

Audrey Vanhaudenhuyse: Yes, we also took what we call the absorption measure to find out how much the participant is absorbed in the experience he or she is having. In this study, Corine showed a much higher level of absorption than when she was in a normal state of consciousness. Similarly, the dissociation measure is used to show how dissociated we feel from reality in the here and now, or how much we can experience bodily dissociations, such as the impression that our limbs are lengthening or deforming. It is known that in a hypnotic state, people show a higher level of dissociation. In Corine’s trance state, we also observed an increased level of dissociation compared to when she was not in trance. But this experiment was only carried out on Corine, we cannot generalize all this yet.

ME e-mag: So you will be working on a group study?

Olivia Gosseries: Yes, absolutely, that’s why we are currently working on a second study, a group study this time, to see if what we observed in Corine is the same for everyone or if there are variations between individuals. The participants are 27 experts in cognitive trance, whom we found via Corine and who were trained by her so as not to mix the trance methods—it will be a next step to be able to compare the different types of trance. For this second study, which has not been published yet, we have for the moment simply focused on the observation of brain activity in trance without adding any brain stimulation. But we have added control conditions: a condition where the person has to imagine a previous trance, and a condition where he or she hears auditory stimuli. We are trying to find out if the trance is more a matter of imagination or a real perception of things. Each time, we ask the participants what happened during the trance, what they saw, etc.

ME e-mag: Is one of your objectives also to compare trance, hypnosis and meditation states?

Audrey Vanhaudenhuyse: Yes, and maybe even other techniques because they are all techniques that allow you to put yourself in a modified state of consciousness but the subjective experience is different each time. Hypnosis and meditation are very mental, whereas cognitive trance is very corporeal, so the experience is different for each person. It seems that cognitive trance allows you to develop a greater connection with the environment, nature, etc.

Olivia Gosseries: Corine also says that in the trance state she feels more strength. In Mongolia, for example, she could hold and bang her huge drum for a very long time in the trance state, which she would not have had the strength to do in a non-trance state. She also says that she feels less pain during trance compared to her normal state of consciousness. So we are working to find out if it is really an increase in strength and potential, or if it is rather a subjective feeling but without difference on an objective level.

04. Finding Clinical Applications

ME e-mag: What are the clinical applications that trance could lead to?

Audrey Vanhaudenhuyse: We started a clinical study in January in oncology, to see if trance could have beneficial effects on quality of life, sleep, emotional regulation or treatment side effects. We have received funding from the Télévie and the Fondation contre le Cancer and we have hired a post-doctoral researcher, Charlotte Grégoire, who will coordinate the oncology study. This project will take place over a period of four years with patients who have had cancer, who have completed their treatment within the last year (chemotherapy, radiotherapy) and who do not have a regular practice of meditation, hypnosis or trance so that it does not distort things. Then, we offer them the option of learning either the hypnosis technique, or the meditation technique, or the trance technique. They follow a training course in the technique they have chosen according to their preference in order to become able to induce hypnosis or meditation or trance themselves.

At the same time, we have started to work on a second clinical application related to patients suffering from chronic pain. Could trance help relieve their pain? Patients will learn a technique and we will then follow their evolution over time to see the effects of these techniques on their pain. These two clinical applications are in line with studies we have already done on hypnosis.

ME e-mag: Can the trance state give us keys to other neurological pathologies linked to the brain such as schizophrenia?

Audrey Vanhaudenhuyse: That’s one of the big questions, to see if there are similarities between things experienced during cognitive trance and hallucinations of patients with schizophrenia. Corine works with psychiatric hospitals. But trance can be such a powerful tool that it can cause decompensation or increase the existing symptom for the time of the trance, so you have to put a clear medical framework around it to protect patients. What is clear to me is that trance, hypnosis and meditation are tools that allow us to find hidden potential and resources that we have forgotten or that we have never learned to use because it was not part of our culture. The objective is to give the power back to the person to find resources within himself or herself to get better, as a complement to traditional medicine.

05. Everybody Can Experience Trance

ME e-mag: Does everyone have the ability to go into a trance?

Audrey Vanhaudenhuyse: According to Corine, cognitive trance is a potential that we all have within us, so most of us can experience this state. So the majority of our patients should be able to do it after their training.

Olivia Gosseries: For the trance training given by Corine, she offers four days during which she uses a sound loop— electronic designed sounds, voices, noises—and this allows people to enter into trance. According to her, 90% of the people she trains are able to enter a trance. Then she teaches them to induce the trance without a sound loop, simply by finding a movement or something that makes the person, by practicing, manage to self-induce the trance when they want and where they want.

Audrey Vanhaudenhuyse: This is an expertise that we have already had in hypnosis for several years and studies have shown that learning self-hypnosis allowed oncology patients to reduce pain, anxiety, and improve their quality of life. We have sufficient experience with this and we are trying to apply it to other techniques such as trance.

ME e-mag: Is it difficult to bring the topic of trance into the scientific world?

Audrey Vanhaudenhuyse: There are a few studies on shamanic trances but not many. It is quite a long process. For hypnosis, it took 20 years for it to become much more legitimate and today it has become more common even if it is not yet universally accepted. For example, there is not yet any recognition of the title of hypnotherapist. Meditation also took time before it could be established in scientific studies and clinical applications. Trance is a continuation of these tools.

Olivia Gosseries: Dr. Michael Hove, an associate professor at the Fitchburg State University, published a paper on shamanic trance with Harner’s method but he had a hard time publishing his paper. He finally managed to do so in 2019 by changing the title and talking about an “absorptive state of consciousness” instead of trance. So clearly there are still barriers. In our case, we called it cognitive trance and we explained that it is inherited from the shamanic practice but that there are no more rituals involved.